Carbon or harm? The price of the risk of anthropogenic global warming

[First published in 2008]

Summary

The causes, consequences, mechanisms and extent of anthropogenic global warming (AGW) are uncertain, as is the optimum balance of mitigation and adaptation in response. That balance is achieved where the marginal costs of (a) mitigation, (b) adaptation and (c) inaction are equal. Discovery in an appropriately-structured market is a better way than calculation to establish prices and volumes of complex, diffuse, uncertain and evolving risks. Popular mechanisms (e.g. cap-and-trade or carbon tax) produce distorted outcomes by fixing in advance those things (volume or price) which the market exists to establish.

This paper argues that the market should not host trades in a notional commodity (a quantum of reduction in output of CO2 from certain sources), but rather in the risks associated with AGW. The cost of factors that affect these risks is the cost of liability for future damage attributable to AGW. The present cost of future liability is the cost of insuring with substantial counter-parties against that liability.

A mechanism is proposed to match the emission of a volume of greenhouse gases (GHGs) with the liability for a proportionate share of any consequential damage. The mechanism establishes the annual volume of permissible emissions (net of absorption) that participants in the market judge to represent the balance of risk (cost of liability) and reward (sale of emissions permits).

National governments are responsible for accounting for the permits for the annual net emissions within their boundaries. They have significant influence over the permitted level of emissions, and their means of achieving the necessary balance of emissions and permits is not constrained. The market is open to private as well as public participants.

Liability is depreciated over time in parallel with the absorption of the GHGs. An approach is suggested for quantifying the costs for which those who hold the liability are responsible.

Brief consideration is given to some risks and weaknesses of the proposal, and to aspects needing further investigation.

Pros (++) and Cons (--):

Structurally, the proposal offers mostly advantages over currently-favoured mechanisms.

- Price and volume will react quickly and strongly to changes in understanding and conditions (++).

- Both adaptation and mitigation are incentivized without preference (++).

- Carbon sinks are valued proportionately, providing incentives to preserve and enhance them (++).

- Centuries of experience in managing risks in efficient insurance-markets are leveraged (++).

- Each nation has greater autonomy to decide how to respond to the market signals (++).

- The value of low emissions and high absorption in many undeveloped countries is recognized, helping them to develop but to do so efficiently (++).

- Commercial organizations (e.g. insurers) as well as governments have incentives to support research (++).

- Researchers' focus and emphasis should move from the worst case to the most likely case (++).

- An incentive is created for those holding liabilities to reduce them by funding adaptation measures (++), but

- no suggestion is provided for how such investments would avoid free-rider problems (--).

- Certain types of emissions (e.g. some methane) may be hard to accommodate (--).

Politically, the proposal has strengths and weaknesses. It requires a complete rupture with the current approach embodied in the Kyoto Protocol.

- Politicians may wish to avoid starting again (--), and

- a change will be opposed by the many vested interests that have been created by the mechanisms established in the wake of Kyoto (--). On the other hand,

- the failings of the Kyoto approach are inherent in the concept and cannot be removed by refining the implementation. A clean break and fresh start based on a concept that more accurately reflects the reality of AGW may be the only way to achieve broader agreement and realistic action (++).

- The proposal should be more attractive than Kyoto to:

- undeveloped nations, who should be able to use it as a source of revenue and spur to outside investment (++),

- developing nations, whose demands that rich nations be responsible for their legacy are taken into account (++), and

- heavy emitters in the developed world, who can more easily strike a balance between the costs and benefits of various measures than under a Kyoto-style mechanism (++).

1. Facing the risk

There is a risk, the scale of which is subject to uncertainty and differences of opinion, that human emissions of greenhouse gases are changing the climate in ways that may have consequences (positive and negative) of uncertain magnitude at unknown dates in the future.

This effect occurs at a global scale, but there is a disparity between nations (and individuals) in their contribution to the emissions, their vulnerability to the risk and their perception of its probability and severity. Any solution will require broad international agreement. To have a chance of gaining broad support, that agreement will have to incorporate flexibility to allow different governments to deal with the problem in their own ways, whilst providing assurance that the burden is not being exaggerated or understated, and is being shared as fairly as possible. It will not be possible to provide that flexibility and assurance unless the solution takes account of the differences in perception.

Whether based on “cap-and-trade”, “carbon tax”, regulation or technology, most mechanisms proposed for tackling the threat of anthropogenic global warming (AGW) rely on the arbitrary selection by central agencies of an optimum profile of emissions, and/or price of carbon, and/or shares of the burden. They confront very great difficulties of coordination and trust (the “prisoner's dilemma” writ large) between nations, as may be expected of political solutions not rooted in sound economics (i.e. trying to override rather than harnessing people's interests and subjective impressions). This paper presents an alternative.

As many national governments are determined to retain control of the methods used to respond to this risk within their national boundaries, markets are likely to remain the most acceptable and practical means of achieving international coordination. However, the market structures deployed so far require a significant surrender of this independence, rely on the decision of central-coordinating agencies about the optimum profile, and second-guessing of and political unanimity on the appropriate sharing of that profile between nations and between solutions. These features inhibit the emergence of rational price signals; effective markets need the freedom to discover exactly those things that are being pre-judged in the EU-ETS and other such schemes.

The problem is that people have been trying to create the wrong types of market. This is not a commodity market – it is a risk market.

The external cost of carbon-emissions is equal to the share of those emissions in the cost of any ensuing damage, or in the cost of preventing that damage (whichever is lower). The net present value of that external cost is equal to the price required to make sufficient provision for the liability for the risk of that damage or the responsibility for its prevention. Carbon does not have an innate value or cost of its own that is separate from the consequences of its release into the atmosphere. Its cost is that required to persuade someone of sufficient financial standing to underwrite that risk.1 The underwriters themselves will use a variety of methods and perspectives to estimate their liabilities and risks. The diversity of the market will provide a more balanced and responsive price than the calculations of one central agency. The objective should be to create a market that provides this insurance and charges its cost proportionately to those whose actions contribute, positively or negatively, to the risk.

2. A suggested approach to a new market for global-warming risks

The following suggestion for the outline structure of an international mechanism to trade the risks of global warming focuses initially on carbon dioxide as a prime example, but it should be remembered that other significant greenhouse-gases (other than water-vapour) should be incorporated within the mechanism on an equivalent basis (see Section 5 below). The basic elements of the market would be as follows:

-

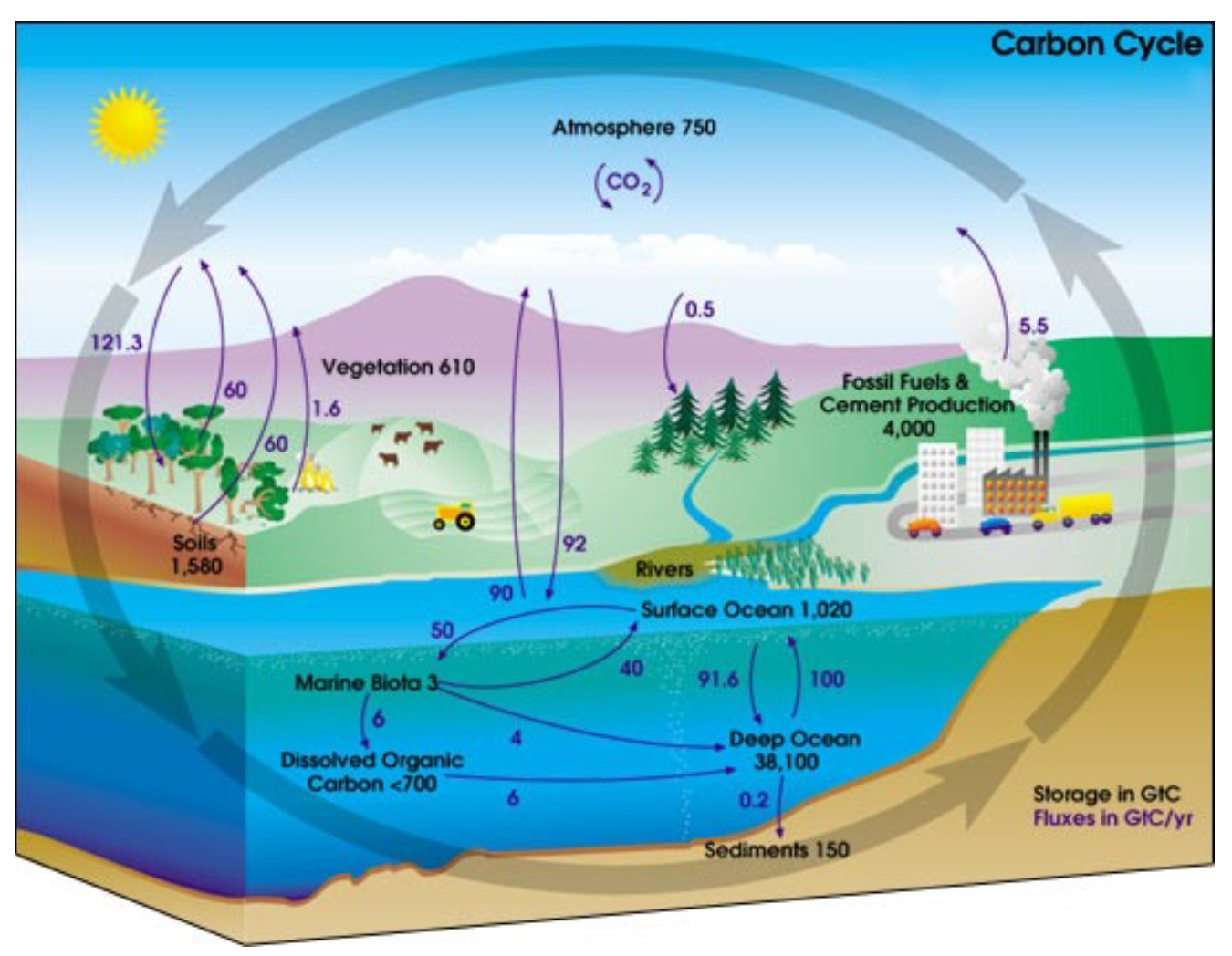

A process is agreed internationally for assessing national, annual, net emissions of each greenhouse gas for each country. It will take account of sources of carbon dioxide (e.g. the combustion of fossil-fuels and biomass, composting etc.), methane (e.g. coal-mines, landfills, farms etc), nitrogen oxide (e.g. vehicles and other combustion plant) and other significant greenhouse gases, and of biological, chemical and mechanical carbon-sinks (e.g. forests, seas, or carbon-entombment). These assessments are already, by and large, being carried out for the purpose of understanding the processes that affect our climate.

-

National governments agree that they will present excess-emission credits (see below) annually in proportion to their net emissions.

-

An international agency offers, on an annual basis, paired excess-emission credits and excess-emission liabilities. These are a pair of certificates, denominated in a certain mass of carbon dioxide (say 10 ktC [thousand tonnes of carbon]). The credits can be used, ultimately, by national governments to satisfy their obligation from the previous paragraph. The liabilities denote the acceptance by their possessor of their obligation to pay towards the cost of repairing the damage from any climate-change impact, above a baseline level of severity and incidence (see Section 6 below), in proportion to their share of total issued outstanding liabilities.

-

The paired certificates are neither bought nor sold nor limited on first offering. A bidding period for initial issuance of that year's certificates (the initial market) is defined, during which eligible organizations (public and commercial) declare what volume of credit/liability pairs they would like to take. All declarations are visible to all other participants in the process, and can be adjusted until the close of the bidding period, at which point the organizations are bound to take the number of credit/liability pairs in their closing bid.

-

The total number of excess-emission credits taken by all parties represents the total volume of net emissions that can be emitted globally that year. The total number of excess-emission liabilities represents the combined responsibility for the costs of any above-baseline climate impacts attributable to that year's global net emissions.2 Participants in the initial market will want to ensure that the potential cost of the liabilities (established either directly by actuarial calculation, or indirectly by laying off the risk to commercial underwriters) is less than the value of the credits to the operators of the various processes that cause emissions (the polluters).

There is much more detail to be considered, but it should already be possible to discern the fundamental strengths and weaknesses. Relative to existing mechanisms, it can be seen that this basic structure more effectively:

-

Discovers the economically-efficient level of total carbon-emissions;

-

Takes account of differences in national perspectives and circumstances to achieve their most efficient distribution; and

-

Makes provision for those who may be affected by the consequences of the emissions.

This approach is more economically-efficient because it allows costs and benefits of mitigation, and adaptation to be weighed against each other. The marginal value of additional credits falls as the total number of credits issued increases, particularly as the volume approaches, first, the level at which demand could be reduced by easy (i.e. cheap) carbon-savings, and even more strongly as the level approaches the level of current emissions. The marginal cost of additional liabilities does not fall as strongly, and may hold steady or increase, as the total number of liabilities issued increases, because subjective judgements of the risk will take account of the possibility of non-linear aspects of the effects of GHGs on climate-change (“tipping points”, “feedback loops”, etc) as well as the simple cumulative effect on the probability of impact from increased volumes of emissions. The market should gravitate towards the point at which the total number of credit/liability pairs results in a balance between the value of credits and the cost of the liabilities. This point, by definition, represents the level of emissions at which the carbon-cost of adaptation balances against the carbon-cost of mitigation. The mechanism thereby establishes the most economically-efficient level of emissions, without resort to central calculations.

3. Internalizing the international mechanism within national boundaries

Nations may choose their own ways of internalizing this mechanism to their own economies. No agreement is required on a unified international mechanism for carbon-trading, taxation or any other approach, beyond the establishment of volumes of allowable emissions in the initial market. The options include:

-

The simplest approach, which will be adopted by more centrally-planned economies, will be for governments to estimate their potential net emissions and bid for the necessary number of liability/credit pairs to match those emissions. They will retain the liabilities within government, and pass on the costs of providing for that liability in whatever way they see fit (these may simply be socialized in the most socialist of economies).

-

Mixed-economy governments may take a similar initial approach to the first option, but might alternatively choose to lay off the liabilities and/or sell the credits. The laying off of the liabilities would establish the cost that should be recovered from those whose processes contribute to the net emissions. The selling of credits could be used to pass on that cost to polluters. Such governments may also choose to take a minimum baseline of credit/liability pairs and rely on traders to take the marginal, uncertain volumes, buying back (at necessarily elevated cost) whatever volume is needed to balance the books at the end of the year

-

Market-economy governments may choose to delegate responsibility to polluters and traders from the start. A government could place an obligation on the polluters to surrender credits in proportion to their emissions. Larger polluters may choose to bid directly for credit/liability pairs in the initial market, while financial institutions will also bid for volumes to sell to larger and smaller polluters who are unwilling or unable to trade directly.

Whichever approach were used to internalize the international mechanism, governments would have complete freedom to determine the methods they would use to ensure that they achieve the necessary level of net emissions.

Those governments that are more sanguine about future risks and costs may choose not to apply tight constraints to their emissions, on the basis that they take a larger share of the future liability. Their subjective judgement will be that their more cautious rivals have imposed unnecessary costs on their economies, and should therefore feel that they have achieved a good deal from the process.

Those governments that are more worried about future risks may reduce their exposure by taking fewer credits and liabilities, but will then be obliged to find ways to reduce their emissions to match. Their subjective judgement will be that their more sceptical rivals have taken on an unwise share of the future costs, and should therefore feel that they have achieved a good deal from the process.

It is possible that governments of more sanguine countries may choose to buy credit/liability pairs beyond their requirements, planning to re-sell some of the credits to less sanguine governments, on the basis that the former place a lower value on the liabilities than the latter, and can therefore profit to both parties' advantage from selling on the credits while retaining the liabilities. This offers real potential for reducing the tensions between governments with different perspectives on AGW.

Governments of poorer nations exposed to risks of damage from climate change would have, for the first time, a mechanism by which they could recoup costs resulting from climate-change. They should feel pleased not only that this marks a significant improvement on their current position, but also that the associated increase in certainty about the future will allow greater confidence in investment to develop their economies. They would have an incentive to develop in a way that minimizes the increases in their carbon-emissions, so as to retain their position as beneficiaries of this mechanism. And they would have an indication from the market of the real cost of carbon, and therefore of which low-carbon investments are genuinely worthwhile, and which are merely vanity projects that are inappropriate to developing nations.

Given the difficulty of predicting precisely the number of credits required each year, national governments will be likely to find themselves with a surplus or a shortfall of credits at year-ends. The first recourse will be for those with a surplus to trade with those with a shortfall. But there are still likely to be imbalances at a global scale.

If there is an overall shortfall, those who cannot submit sufficient credits will be obliged to accept additional liability certificates in proportion to double their shortfall. This would provide the incentive for people to make an honest attempt to estimate

their emissions rather than leaving it to year-end to correct retrospectively – an important constraint if the initial market is to provide a reasonably accurate guide to perceptions of risk and cost attributable to carbon emissions. This also places a cap on the tradeable value of surplus credits – if those possessing surplus credits try to charge the equivalent of more than double the cost of the associated liability, those with a shortfall will choose instead to take the extra liability.

If there is an overall surplus, those with excess credits should be able to bank them for use or trading in the following year.

4. Accounting for national and international carbon-absorption

One of the objectives of basing the mechanism around net rather than gross emissions is to put a real value on carbon-sinks and thereby to provide proportionate incentives for their protection (in the case of natural sinks) or development (in the case of manmade sinks). Many sinks (such as forests and those that rely on absorption of GHGs in coastal waters) lie within national boundaries. It is desirable to attribute the capacities of these sinks to the countries within which they are located, so that their national governments have an incentive to put an appropriate value on them in whatever mechanism they use to internalize the carbon market. Thus the owners and occupiers of the sinks will, in turn, have an incentive to preserve and enhance them, to balance the incentives associated with other possible actions, for example to replace forest with an activity (such as farming) that provides a return.

Some carbon-absorption, however, occurs in international waters. At present, it is estimated that the ocean (including national and international waters) absorbs around 2 GtC (billion tonnes of carbon) annually. At this rate, the ocean is acidifying, and not all that absorption can be attributed to international waters, but it might be reasonable to allocate (say) 1.2 GtC as the volume of carbon that can be absorbed sustainably by international waters. This represents approximately 0.2 tC per person. For political reasons, and in the absence of a more rational alternative, it is suggested that shares of this international absorption-capacity be allocated to each nation in proportion to their population. If so, a country with a population of 60 million people would have scope to emit 12 MtC (million tonnes of carbon) without its net emissions exceeding zero, even before taking into account any national carbon-sinks.

Allocation in this way means that the poorest nations will not need to take on any credit/liability pairs, and indeed will be able to trade the difference between their allowable emissions and their actual emissions with any net emitters. This effect will be enhanced by the fact that many of the poorer countries enjoy a good share of the land-based carbon-sinks (typically forests), which will further increase the volume of unused emissions-credits that they can trade.

5. Temporal aggregation and depreciation

Let us now return to a complication that was postponed earlier. One cannot isolate the impact of carbon-emissions in a particular year – any damage that results from global warming will be the result of emissions over many years. Liability therefore needs to be allocated to holders of liability certificates related to emissions in all relevant preceding years.

Emissions do not remain in the atmosphere for ever. They are gradually reabsorbed.3 One can say, in effect, that the contribution of a tonne of carbon in Year 2 is less than it is in Year 1 after emission. The liability certificates should indicate the absorption rate that was applicable in the year of emission for the gas in question. As each year's liability certificates are added to those of the previous years, the total share of liability is spread thinner, and the share attributable to the earlier certificates is reduced in accordance with their absorption rate.

An example may make this easier to understand. Let us say that only three organizations (A, B and C) are taking credit/liability pairs, and that we are only dealing with carbon dioxide, which has (for the sake of argument) a linear absorption rate of 1 per cent/year (i.e. a lifespan of 100 years). In Year 1, Organization A takes 1,000 MtC, B takes 1,500 MtC and C takes 2,500 MtC. Their shares of the liability, if it were isolated to that year would be 20, 30 and 50 per cent respectively. In Year 2, A takes 1,000 MtC again, but B and C each take 2,000 MtC. Their shares from the liability from that year would be 20, 40 and 40 per cent respectively, but we must also take into account the remaining liability attributable to emissions in Year 1. These have been absorbed a little, so their contribution to the combined liability for both years is now 4,950 MtC.

Liability will be shared in proportion to the total combined liability of 9,950 MtC (4,950 MtC for Year 1 and 5,000 MtC for Year 2). Organization A's liability at this point is 990 MtC from Year 1 and 1,000 MtC from Year 2, or 20 per cent (exactly) of the 9,950 MtC. B's liability is 1,485 MtC from Year 1 and 2,000 MtC from Year 2, or just over 35 per cent. C's liability is 2,475 MtC from Year 1 and 2,000 MtC from Year 2, or just under 45%.

| Year 1 | A | B | C | Total |

| Emissions (MtC) | 1,000 | 1,500 | 2,500 | 5,000 |

| Share (per cent) | 20 | 30 | 50 | 100 |

| Year 2 | ||||

| Emissions (MtC) | 1,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 5,000 |

| Y1 emissions “depreciated” | 990 | 1,485 | 2,475 | 4,950 |

| Remaining emissions (Y1 + Y2) | 1,990 | 3,485 | 4,475 | 9,950 |

| Share (per cent) | 20 | 35.03 | 44.97 | 100 |

The organizations can adjust their share of the liability by reducing or increasing the shares that they take in each year, and if they stop taking credit/liability pairs, their liability will degrade to nothing over time. But they will retain some share of the liability for as long as the emissions for which they were responsible are retained in the atmosphere.

An under-appreciated but important component of AGW theory is that different greenhouse gases have different average lifespans of retention in the atmosphere. When we quote a Global Warming Potential (relative to carbon dioxide) of 23 for methane, that is an arbitrary figure taken over a 100-year time horizon. In fact, methane's instantaneous contribution to radiative forcing is approximately 100 times greater than that of carbon dioxide, but because it is reabsorbed much more quickly, some adjustment has to be made to allow for this factor. This adjustment distorts policy. If one considers that methane emissions today have a much stronger impact on warming in the near future than is usually imagined, the obvious reaction, particularly if one were worried about tipping points, would be to target methane emissions more strongly than we have done until now on the basis of the false generalization that its impact is only 23 times that of carbon dioxide. If, on the other hand, one felt that disaster was relatively distant, one would place a relatively low cost on methane emissions, because their impact would have dissipated before their effect was felt.

The proposed mechanism can take account of this reality, and therefore direct efforts in the most beneficial directions, in a way that other mechanisms cannot. The credit/liability pairs will be for specific gases. The credit will entitle the emission of a specific volume of a specific gas. The liability will attribute responsibility in propo tion to the carbon-equivalence of the credited volume of the specified gas, but will have an associated absorption rate (similar to a rate of depreciation) that is applicable to the gas in question. In the case of methane, if it were linear (for the sake of simplicity), it would be around 8 per cent of the original carbon-equivalence each year, as methane's average lifespan in the atmosphere is only around 12 years. In the case of nitrous oxide, whose average lifespan is around 120 years, the absorption rate would be less than 1 per cent of the original carbon-equivalence each year. Those who would rather take a large share of short-term risk but limit their exposure to long-term risk will prefer to take certificate-pairs for methane than those for carbon dioxide or nitrous oxide. Those who would rather spread their risk thinner over a longer period of time will prefer to take pairs for carbon-dioxide or nitrous-oxide than for methane. These preferences will be affected by developments in the understanding of the severity and imminence of the threat. The mechanism would provide the right incentives for people to respond in rational ways to the latest science.

This effect can also be used to reduce one of the significant tensions in international negotiations. The developing nations point out that the vast majority of anthropogenic greenhouse gases currently resident in the atmosphere are attributable to the developed nations, and that they therefore ought to take the lion's share of responsibility at this stage. The developed nations point out that, if growth continues on its current pattern, the emissions from the developing nations look likely to dwarf their own emissions, and that placing all the onus on the developed nations will not only place an unbearable economic strain on their economies, but will be wholly ineffective if some constraint is not also placed on emissions from the developing nations. Both sides are right, but the necessity under current mechanisms to agree a hard cap and hard shares of allocations within that cap, makes it difficult to find an acceptable compromise.

Under the proposed system, all governments would be expected to take responsibility for their historical net emissions of the various greenhouse gases going back however far is relevant for the gas in question (e.g. 12 years for methane, 120 for nitrous oxide). A cut-off at (say) 1900 might be agreed as a date before which (a) estimates

may not be reliable, and (b) the current impact is likely to be de minimis. Given the depreciation in impact caused by the absorption-rates, the most recent emissions will be proportionately more significant than earlier emissions. If major impacts are felt in the near future, the developed world will have to pick up most of the bill for the costs of those impacts. But for impacts further into the future, which are likely to be the lion's share of impacts, liability will be spread increasingly closely in proportion to current emissions. This should satisfy the developing nations' demands that developed nations take responsibility for their historical emissions, without saddling developed nations with a disproportionate share of the burden going forward, and providing strong incentives for both developed and developing nations to develop their economies as efficiently and cleanly as possible.

6. Estimating liabilities

And so to the most difficult and contentious part of the proposal: the liability. It is all very well to say that liability should be shared in proportion to emissions, but liability for what? Which impacts ought to be covered, and how should the cost of the liability be calculated? Ignoring for the moment the possibility that rising temperatures may not be caused primarily by human activity (we return to this issue below), some impacts, such as flooding due to rising sea-levels, are obviously a consequence of global warming and therefore their costs should fall on those holding the liability. But others are less certain: inland flooding or drought may be caused by bad development, irresponsible agricultural practices or even simple economic collapse, as well as by atmospheric conditions. Even where atmospheric conditions contribute, the effects can often be mitigated by sensible provision (e.g. flood defences, stores of food and water). People and governments should not be absolved from responsibility to make what provisions they can, nor should they be insulated from the costs of failing to do so.

Then there is the common case where people have ignored risks and exacerbated the consequences of disaster. If (for sake of example) more frequent and severe hurricanes were a consequence of global warming, should those carrying the liability have to shoulder the full cost of damage to the ever-more-expensive properties that sprout up irrationally along the USA's South-East seaboard? Clearly not. If you are foolish enough to build or purchase a property in a known hurricane-zone, you should shoulder the cost of insuring the predictable damage.

Let us start by returning to that particularly awkward consideration – that rising temperatures may yet turn out to be caused more by natural causes (e.g. solar activity) than by human activities. Mechanisms that cap emissions and value only carbon-reductions would have been spectacularly pointless and wasteful in those circumstances. And yet, action might still be required, because the consequences of rising temperatures might still need to be considered.

If warming were caused by solar activity rather than by anthropogenic carbon-emissions, it would not reduce the risk that large parts of Bangladesh might be flooded.4 Simple humanity would require that we still, in those circumstances, place a value on defending against the consequences of the warming. If severe flooding of a country like Bangladesh were to occur due to rising sea-levels, the international community would be called on to assist. The obligation to assist might reasonably be apportioned relative to economic capacity. The historic level of carbon-emissions would be a reasonable guide to each country's economic capacity and therefore its moral obligation regardless of causation of the damage.

It may be no bad thing to develop a mechanism that determines in advance where the cost of such damage would fall, and apportions it roughly in proportion to economic capability, even if there is dispute about the cause and therefore responsibility for that damage. It is justifiable, on this basis, to include within the liability covered by this mechanism the responsibility for those extraordinary impacts predicted by AGW theory, regardless of whether the connection is perfectly proven. The underwriting of the liability under this mechanism becomes an underwriting of the cost of certain major disasters regardless of cause.

So which impacts might we include on that basis? Some are not controversial, in the sense that they are definitely a consequence of warming, whatever the causes of that warming, e.g.

-

Flooding due to rising sea-levels.

-

Consequences of changes to precipitation outside the normal range of variation

(e.g. dryer summers, wetter winters in temperate latitudes).

-

Falling river-flows due to the disappearance of glaciers (and associated consequences, e.g. crop-failure and drying of vegetation leading to fires).

-

Erosion and other damage due to loss of permafrost (e.g. large chunks of some mountains are collapsing as ice melts, which may cause damage in some situations).

-

Habitat destruction and loss of livelihood in those places and for those activities dependent on winter snow.

Other potential impacts are more controversial, for example the potential reduction in the flow of the North-Atlantic conveyor, and the consequent changes to climates on both sides of the North Atlantic, or the incidence and severity of hurricanes. A commission should be established to assess which risks are credible (not their likelihood and probable scale), and for each risk, to establish a historical baseline and range of normal variance. Being based on possibility not probability, and historical not projected data, this should allow very much less scope for the imposition of subjective judgements than within the IPCC/Kyoto mechanisms.

For each of these impacts, the commission would establish a historical baseline, how that baseline has moved over time, and a range of normal variance around that travelling baseline. For example, if increased incidence or severity of hurricanes were a credible risk, the commission would establish the average incidence of hurricanes (how many and of what grade) in (say) 1900 in each area that is exposed to hurricane-risk, the annual variance of this incidence and severity, and how that average and variance had changed over time since 1900. Liability under this scheme would not apply to damage to properties from hurricanes that were within the historic range of variance for the period when the property was built. Such damage would be the domain of private household insurance. But where repeated damage occurs due to a hurricane season that has more hurricanes of a particular grade than would fall within the normal range of variance for the construction-date, the liability for the costs of damage from

any hurricanes that exceed the norm will fall on those holding the liability certificates, in proportion to their share of the liability in the year in which the damage occurs.

To allow for establishment of a meaningful range of variance, this baseline and variance will have to be calculated over reasonable intervals. Given the climate cycles that are known to occur due to solar activity, intervals of less than 15 years are probably not practical, while intervals of 50 years or more might smooth-out the twentieth-century climate changes to too great a degree to give a meaningful figure. 20-year periods might be a reasonable compromise. If so, the initial baseline and variance would be established on the basis of historical patterns between 1900 and 1920, and updated figures would be calculated for the periods 1920-40, 1940-60 and so on. Liability for damage attributable to events outside the 1900-20 range of variance would be incurred on those properties built before 1920. If the upper-bound of the range of variance had increased during the 1920-40 period, those properties built after 1920 would not be covered for damage from some events for which properties built before then were covered. This would leave everyone covered for damage due to events that were not predictable at the time the property was built, but responsible for their own cover for any events that were predictable at the time the property was built.

With baselines and variances established, an international agency (perhaps the same as the issuing agency) could be made responsible for receiving, verifying, and arranging for the assessment of claims for damage from events outside the relevant variances. Verification would consist of confirming that the events were outside the normal bounds, as claimed. Assessment would consist of costing the damage that is covered, once liability had been established. The latter could be subcontracted to assessors on the usual basis. Once assessments had been received, the agency would be responsible for notifying all holders of liability-certificates of the share of the underwriting-cost that was required from them, and for disbursing those funds.

To avoid thousands of small claims being handled directly by the central agency, the agency should only accept claims from licensed intermediary organizations, who would compile claims from an event and submit the aggregated claim to the agency. The intermediaries would pay a substantial agreed sum to the agency for the license to be able to act in this capacity, to provide a significant source of funding for the agency's operations, and to ensure that only substantial organizations can act in this way.

In many cases, the intermediaries might be government agencies, but there should be scope for commercial bodies also to act in this capacity. The intermediaries may be funded from taxation (e.g. if state-run bodies) or from fees charged to those placing claims. The presence of commercial as well as state-run intermediaries will be important to minimize abuse of the system by third-world governments, some of whom may be tempted to submit claims on behalf of their people to the agency, but fail to fully disburse the sums received. It should be a condition of participation in the scheme that governments permit their people freely to choose through whom to submit their claims. The license of any state-run intermediary should be revoked if clear evidence is presented that the government in question is not allowing a free choice in this way. The license of any intermediary should be revoked if clear evidence is presented that they have failed to disburse the money properly.

7. Minimizing the risk of default

Of course, failures can be accidental as well as deliberate. The greatest risk of accidental destabilisation of the mechanism is the threat that some organizations may take on liability and then be unable or unwilling to cover the costs. As an initial precaution, there ought to be a liquidity requirement for participants in the market – only those who can show that they have sufficient financial standing should be able to take on liabilities, in proportion to their standing (this should apply to governments as well as businesses).

Nevertheless, circumstances can change between the time that liabilities are accepted and the time when the costs are incurred. The sanction that should be applied in order to minimize default is that failure to pay out the amount assessed by the agency should result in the exclusion of that organization (government or business) from further participation until the amounts owing have been paid. For the poor governments who are most likely to default, this is potentially very serious. Such governments are likely to be responsible for nations who are most exposed to the risks, and are also likely to have low emissions. They would be beneficiaries from trading credits as well as from the underwriting of the risk of harm. To be excluded from the trading and insurance benefits would probably be more expensive than the money saved by defaulting.

Commercial organizations would have the same reasons not to default as they do in current insurance markets – their business is in providing cover, so to default is effectively to go out of business. If this were not felt to be sufficient security, one can conceive of a system where the credit/liability pairs have unique IDs, through which the liability associated with a credit can be traced to the government that surrendered the credit. That government could be made the insurer of last resort if the holder of the liability certificate defaults.

The most serious threat would be default by a rich government, which had taken on a significant share of the liability. Ultimately, one cannot guarantee, without recourse to force, that any independent government will honour treaty obligations. But if this mechanism allows developed- and developing-economy governments the greatest freedom to marry their own interests with the collective interests of global economic growth, environmental stability and social responsibility, those governments would have an interest in maintaining the credibility of the mechanism. The alternative would be a return to the policy nationalism that is increasingly popular nowadays. That nationalism tends towards economic isolationism, and towards economic, environmental and social degradation through the diminution of the social cooperation that is key to all improvements in human welfare.

There are no guarantees. But the combination of self-interest in maintaining the integrity of the mechanism, and the diffuse nature of the cover (so the default of one under-writer should have only a marginal impact on the cost to others) should minimize the risk of default. And to the extent that the risk of default remains, those taking on the liabilities will have to price in their assessment of the risk that their share of the overall liabilities may be greater than expected. This will make the availability of credits marginally tighter than it would be if there were no risk of default. That is an appropriate risk for the market to take into account.

8. What next?

This is only a rough outline of an idea. There are doubtless many problems and omissions. For example:

-

Will national governments accept responsibility for their net emissions, when in certain cases, their emissions may be the product of feedback mechanisms exacerbated by general warming? For instance, release of methane from thawing of the Russian tundra, or drying of the Amazon rainforest converting it from a carbon-sink to a carbon-source.

-

What do we do about international emissions, such as release of methyl hydrates from the ocean floor?

-

Perhaps the most significant incomplete aspect is the question of how we encourage investment in adaptation measures. There is a collective-action problem as things stand with this proposal. There is a general incentive to minimize exposure to risk, but any liability-holder investing, for instance, in a sea-wall incurs the full cost but shares the benefit with all other liability-holders.

But at least this proposal confronts these issues and provides a framework within which they can be considered. Existing mechanisms do not and cannot take account of these and many other of the aspects that this proposal has already taken into account. It is, unlike existing carbon markets, a reasonable representation of economic reality. To take a couple of reductio ad absurdam demonstrations, if it turned out that human activity had very little impact on climate, this mechanism could bed down as a way of insuring against certain extreme weather events, whereas existing mechanisms would have been not just pointless but wasteful and counterproductive. If, on the other hand, the most extreme predictions look likely to happen, the apparent risk will make governments and institutions so reluctant to take on liability that it will put a stronger break on emissions than a marginally-reducing cap.

Much more work is required on this proposal. Details need exploring. Gaps need filling in. Problems like those above need resolving. But the first step might be to develop a model that allows the basic system to be tested and scenarios to be run. How will people, placed in the roles of national governments or financial institutions participating in this market, respond to internal (market) and external (scientific and environmental) information? And how will the market respond to them? It needs a model that allows scenarios and behaviours to be tested in the manner of, in effect, a multi-player game.

But in the meantime, it is to be hoped that this paper has demonstrated, if nothing else, that it is possible to conceive of superior alternatives to the “cap-and-trade” approach. We should not proceed, in our discussions on future global-warming mechanisms beyond 2012 (the date of the expiry of the Kyoto Treaty and the end of Phase 2 of the EU-ETS), on the assumption that the best or only practical option is to continue with the existing, broken approach. We can and should do better if we put our minds to it.

Annex A: Annual carbon emissions per capita (2003)

Source: United Nations Millennium Development Goals Indicators: http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Data.aspx

- More precisely, it should be the net cost, balancing the costs against the benefits of greenhouse-gas emissions, but if those who may benefit can take part in the insurance market, they can price that benefit into their offerings.

- Climate impacts will be attributable to the emissions from more than one year. We cover below how this should be taken into account, and the question of the baseline. For the sake of simplicity, we will continue to deal with a single year for the timebeing.

- Or, more precisely, a certain volume of each greenhouse gas can be absorbed each year, so this rate of absorption is spread over all emissions to give a notional absorption rate. This rate may change with changes to the ability of the Earth to absorb a particular gas.

- It has a better chance, as solar activity is likely to be cyclical, but we have seen big as well as small swings in climate before, sufficient to have substantial impacts on sea-levels, so a change of paradigm with regard to global warming would not rule out the possibility of significant flood-risk.