Those involved were in no doubt about the reports’ direct influence on policy. Their lead within National Grid (Janine Freeman, Head of Sustainable Gas Group at the time) notes in her LinkedIn profile that she:[1]

Led an influential piece of analysis to consider the potential for renewable gas (biogas) in the UK. Then went on to work with government and industry to create the appropriate incentives for investment in renewable gas infrastructure in the UK and the US.

The report of Ms Freeman’s appearance before the London Assembly’s Environment Committee in July 2009 illustrates the impact of National Grid’s work and the limited expertise of policymakers discussing the analysis.[2]

A 2009 article in Biomass Magazine similarly records National Grid’s own positive assessment of its influence.[3]

The January 2009 report, titled "The Potential for Renewable Gas in the U.K," has been delivered to the U.K.'s Department of Energy & Climate Change.

"After we published the report, the phones were red-hot with waste companies and local waste management authorities contacting us," says Isobel Rowley, press officer for National Grid. "It certainly rang a bell."

A 2019 study into actor influence on the UK’s heat strategy confirmed National Grid’s influence on heat policy at this time.[4]

It was however suggested by a number of interviewees that National Grid is influential and that their modelling and their annual ‘Future Energy Scenarios’ ‘puts them in quite a strong place’ because of their ability to shape the energy debate (anonymous). Another interviewee explained that National Grid frame arguments based on their importance and role in the energy system, in the interviewee’s words, the ‘you need us’ frame:

‘They've [National Grid] got a lot of power. So the Government's got to talk to the Big Six, well God they have to talk to National Grid. Without National Grid on-side, everything stops.’ (anonymous)

Another interviewee mentioned their ‘crazy biomethane projections which still reverberate today and still get quoted’ (anonymous).[5]

The government’s consultation on a Renewable Energy Strategy in 2008 shortly preceded the publication of the NG/E&Y report in early 2009. There were many supporting documents to the consultation (including one by Ernst & Young).[6]One of them considered alternative uses for biogas such as scrubbing and grid injection.[7] It concluded that:

Biogas upgrade to bio-methane does not appear commercially competitive due to the costs of upgrading and distribution. Although employing these delivery routes (rather than supporting the development of CHP) does yield greater quantities of renewable heat, it does not enhance the carbon savings – indeed these decline quite significantly. Also, the costs of overcoming supply-side barriers are higher than under the alternative option.

Biomethane or biogas injection were notable by their absence from the other documents supporting the consultation.[8]

As early as Feb 2009 (a month after the NG/E&Y report), the position had changed to:[9]

[biogas] can be upgraded to make biomethane, which can be injected directly into the national gas grid. These technologies can play an important role in helping to achieve our ambitions on renewable heat. We will also carry out further work with the industry to overcome the particular challenges faced by these technologies. Given the special characteristics of this technology, the enabling powers in the Energy Act explicitly allow the RHI to support the production of biogas and biomethane.

Industry lobbyists in parliament used the report to petition for more favourable treatment of biomethane in forthcoming legislation. In Lords questions, the minister (Lord Hunt) expressed scepticism about the upper end of NG/E&Y’s projections, but agreed to subsidiary points that the technology should be taken into consideration.[10]

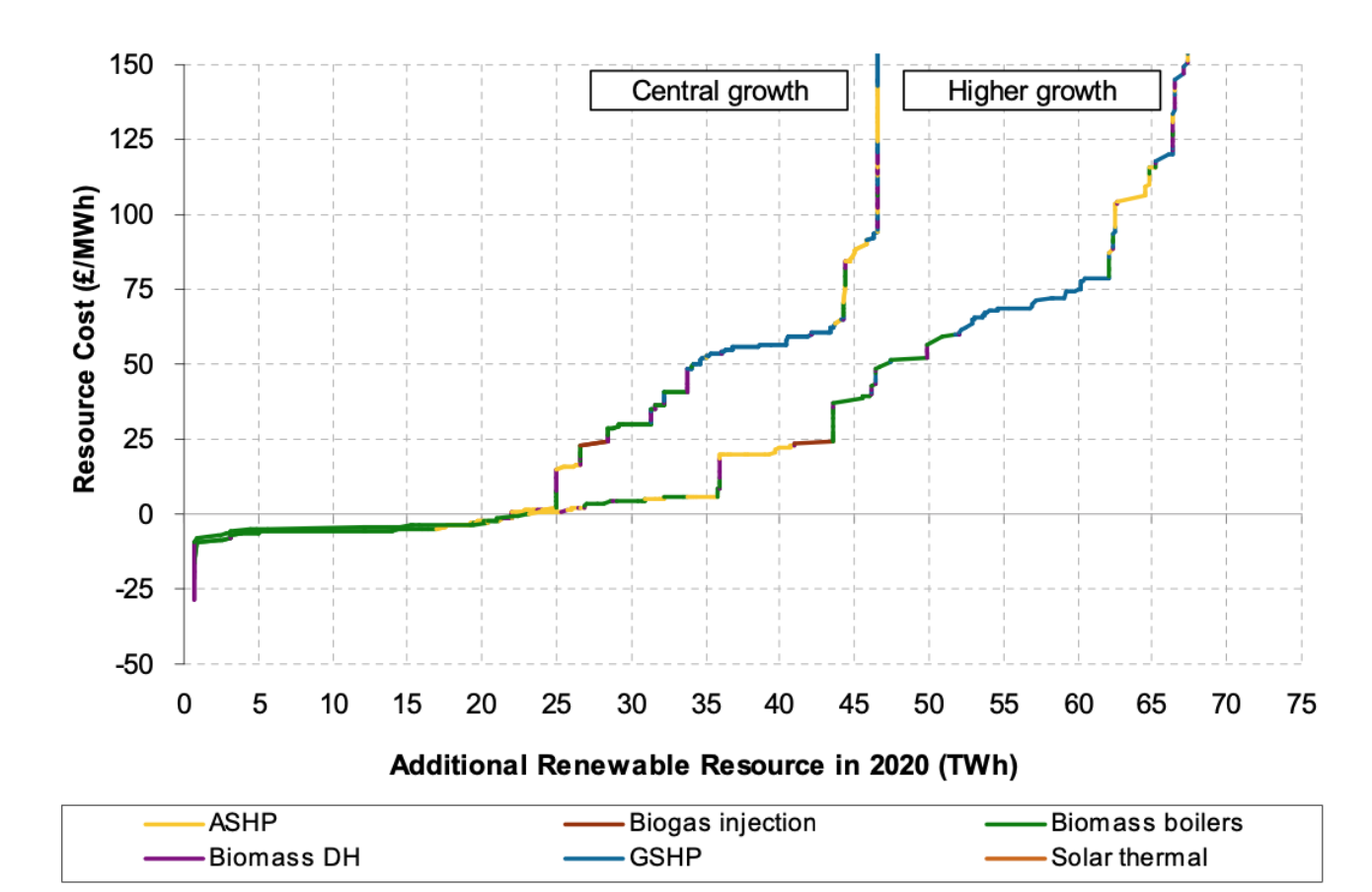

The government published its response to the consultation and the Renewable Energy Strategy itself in summer 2009, after the publication of the NG/E&Y report.[11] Biomethane had become one of the favoured technologies, though its anticipated contribution remained modest. In NERA’s associated study on the UK Renewable Heat Supply Curves, it was expected to contribute around 2.3 – 3.5 TWh at a resource cost of around £25/MWh.

That and the low cost put by the NG/E&Y study on biomethane from food and biodegradable waste probably explains why the original tariff proposed for biomethane in the RHI was relatively low at 4p/kWh.[12]

Richard Lowes describes in his thesis the substantial modifications to the RHI shortly before it was launched, driven by a desire to achieve more cost-effectiveness.[13] One of the changes was to increase the biomethane tariff to 6.5p/kWh, which (along with some other changes) nearly doubled the value of the RHI for this technology. That is not an obvious way to save cost. However, it accompanied a reduction in support (and delivery expectation) for solar thermal and some other changes for smaller (expensive) systems. The logic was presumably that it was better to encourage more large schemes, even if support had to be increased to achieve that, because it was still cheaper than many small schemes. This logic could hardly have applied if DECC had not been persuaded in the meantime that there was more biomethane potential to deliver than initially thought.

By 2012, scepticism was reasserting itself. The Committee on Climate Change’s 2011 Review of Bioenergy expressed strong doubts about National Grid’s estimates of the potential of biomethane.[14] Lowes records that government opinion began to swing in favour of a focus on the electrification of heat. National Grid played a crucial part (as the operator of both key networks) in arguing (a) that full electrification was not practical because of peak demands, and (b) that the gas network was crucial for meeting those peaks.

Lowes queries what role NG would have played, given that they have interests in both electricity and gas. The obvious answers are that (a) they did (as he records), (b) there were other options involving neither grid, which would have been their primary objective to diminish, and (c) they would want to see an ongoing future for both of their networks. Whilst the electricity network was under no threat (given plans to electrify transport as well as heat), it was possible to envisage (because such a model was common in Europe) a heat-decarbonisation model in which gas utilisation fell materially and damaged their returns on that part of their investment. Indeed, Lowes concludes that it was:

clear that National Grid attempted to promote the role of their gas assets throughout the development of UK heat policies and interviewees saw them as an actor with some power in the heat policy debate

[4] Richard Lowes, “Power and heat transformation policy: Actor influence on the development of the UK’s heat strategy and the GB Renewable Heat Incentive with a comparative Dutch case study”, Exeter University PhD thesis. https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10871/38940/LowesR…

[5] Section 9.1.2.3, p.223 passim.

[7] Enviros, Barriers to renewable heat part 2b: analysis of biogas options (Sep 2008) http://www.decc.gov.uk//assets/decc/Consultations/Renewable%20Energy%20…

[8] The Impact Assessment for Renewable Heat refers in a few places to “upgrading biogas”, but a comment on p.8 makes it clear this is referring to “upgrading electricity-only biogas plant to CHP”.

[9] DECC, Heat and Energy Saving Strategy Consultation (Feb 2009) https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uplo…

[11] https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100512180246/http://www.de…

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uplo…

[12] Lowes thesis, Annex 4

[13] Section 8.7: Policy episode 7 – RHI scheme implementation (2011)