If you don't price scarcity, you ration it anyway

Thursday, 8 January 2026

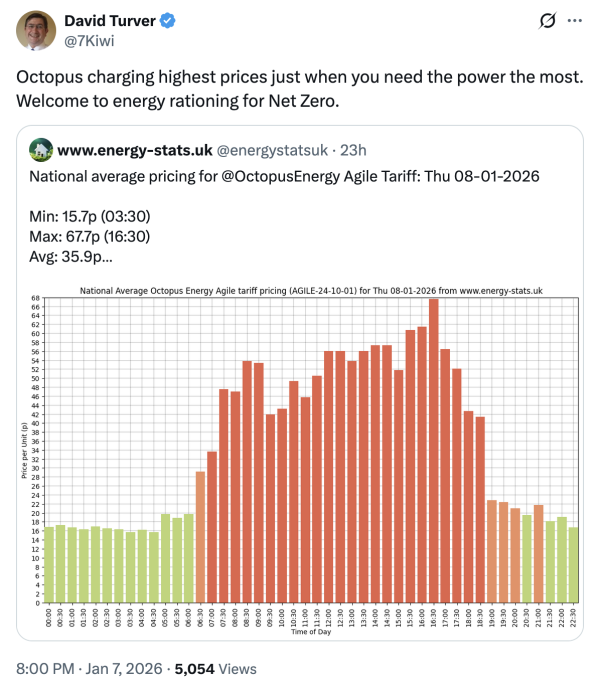

You can buy electricity on Agile prices that reflect the half-hourly balance of supply and demand. Some people think that shouldn't be allowed. They couldn't be more wrong.

Some people who are clear-headed about the bad economics of Net Zero are not so clear-headed about basic economics.

Some think that some economic activity is too important for pricing that reflects supply and demand.

This logic ignores the vast array of choices about the allocation of resources that are embedded in what superficial analysis may judge is a simple strategic judgment.

It also reflects how quickly we forget the lessons of history. This was exactly the logic that led to the gradual nationalisation of the "commanding heights" of the economy post-War, and the UK's ensuing decline. If stuff is important, it's not too important for responsive pricing, it's too important not to price responsively.

The resource allocations that are implicitly ignored include:

Capital

Is it optimal to size the Elizabeth Line to maximum current demand (i.e. idle most of the time), or could the marginal capital for the marginal capacity be put to better use on other infrastructure with greater utility? Economies of scale may mean that max-sizing the Elizabeth Line has a low marginal capital cost. That's probably non-linear, and it still needs to be judged against (a) the value of that marginal capacity (i.e. marginal operating profit), and (b) the value of alternative uses of the capital.

Upstream from there is the allocation of wealth to consumption or saving/investment. Maybe we can max-size the Elizabeth Line and do the other projects. There may be more or less capital available, depending how much people are prepared to pay for it (i.e. interest/return). But there isn’t infinite capital. It is a scarce resource like most things, so there are always choices to be made. Is the marginal value of max-sizing the Elizabeth Line enough to attract the capital against its alternative uses?

Labour

Is the value that is enabled by more people being able to travel on the Elizabeth Line at rush hour worth enough that it justifies the capacity to serve it? Could whatever the marginal traveller is doing have been done elsewhere, or by people who live elsewhere (not needing to travel that route)? Could it have been done at another time (avoiding the need for rush-hour capacity)? Might alternatives to that activity have been acceptable? Is some of it not so valuable that people would still do it if they had to pay the marginal cost of enabling it (and if so, why should other people pay the socialised cost so that they can indulge themselves that way?)?

Infrastructure

Would it be better value to build more housing where people are commuting to? Or build workplaces and services nearer where they live? Or would alternative transport options be better value at the margins? The choice to make it easy to get into London from some areas by train is partly a choice to encourage a particular model (London jobs, Thames Valley rail commuting) over others (London jobs for homes in London or other suburbs, or redistribution of marginal jobs to other regions).

There’s no good reason to tip the balance in favour of London jobs for Thames Valley rail commuters. If that’s people’s preferred option when all costs are fairly weighed, then fine. But the way you weigh those options is for prices to reflect marginal costs and see what people choose. If you insulate people from that pricing, you skew outcomes to a net loss of utility.

Maybe all of the above (and other considerations so numerous that no planner could possibly take them all into account) adds up to a case for max-sizing the Elizabeth Line, but we ought to know, because otherwise some people are subsidising other people’s utility. The way we find out is marginal pricing to balance supply and demand. If people will pay the marginal cost, it was worth investing the capital. If people choose to invest their capital that way, it should be on a judgment that the value will be worth it, and it should be remunerated accordingly.

The complexity is multiplied by the fact that investment decisions need to take account not only of the current situation, but of expectations for how that may change in future. If you think you know the right capacity now for a piece of infrastructure without help of the price mechanism, you are fooling yourself. If you think what you believe now will hold good for the indefinite future without the price mechanism to help respond to changes, there's a reason it was so easy to fool yourself.

Evolution

Sabisky says that the Elizabeth Line is sized for peak demand, but that is a static view. Even without dynamic responses to pricing, it seems a fair bet that demand will not remain static. Once upon a time, planners thought the M25, M60 and M8 would have enough capacity. Conversely, planners once thought the M45, M58 and Humber Bridge were justified by peak usage, or by the economic activity that max-sizing would generate.

Maybe you are a cynic about political decisions, and think the planners never really believed that, and those choices were more a function of political considerations. That’s worse, unless you have figured out a way for political decisions to be immune from political pressures. The altruistic decisions that Sabisky wants to be taken now are not only based on excessive confidence in planners’ knowledge, but also blindness to how well that hypothetical purity will survive the political process that is the alternative to market price-setting.

It’s not even true that the Elizabeth Line is sized for peak now. I live close to the Elizabeth Line, and there have been times when I couldn’t get on. There’s always rationing of scarce resources. If it’s not price rationing, typically it’s queuing.

That’s now. It will change more. Not just because of exogenous factors affecting economic activity and population distribution. But also because you are making peak travel look artificially cheap. Over time, the fact that the benefit of peak travel versus its scarcity is not reflected in its price will result in more people choosing to travel at peak than would otherwise be the case. Over-usage of an under-priced resource is a self-fulfilling prophecy, barring offsetting exogenous factors.

"But it's so unfair that people have to pay high prices when demand is high and supply is scarce."

Trade-offs

Marginal pricing isn’t just about high prices at peak. It is also about low prices off-peak. If you argue for cost-blind pricing, you are arguing as much for over-pricing the off-peak periods as under-pricing the peak periods. The good is badly allocated in both regards - more demand than supply at peak and less demand than could be served off-peak. Opponents of basic economics (let’s be frank, that’s what this is) like the comfort of arguing that expensive things should be artificially cheaper, but never consider the flip-side that they have made the same thing unnecessarily expensive at other times.

Or perhaps you think that those price differentials should still exist between peak and off-peak, but you are just trying to keep the peak price down for social benefit. Now that’s just plain subsidy (under-pricing never offset by over-pricing). That’s supposedly for a social benefit, but it’s actually for a targeted benefit of certain members of society (Thames Valley rail commuters with London jobs) at the cost of the other members of society.

The same logic applies to energy and any other scarce resource.

Price signals help efficient resource allocation

There are many unjustified interferences with resource allocation already, whether that’s Net Zero on energy or planning policy on commuting patterns. We don’t make them better by skewing things yet further. Most of those interventions come from the same mindset (clever central planners can work things out better than market discovery) that thinks governments should ensure flat rather than responsive pricing.

The fact that we have such a (badly) managed economy is not an argument to manage it more (badly). Responsive pricing can help even badly-skewed markets by mitigating the harm. It shouldn’t be limited only to perfectly efficient markets, unless what you really want is no responsive pricing ever, because we will probably be waiting a long time for a market that governments don’t skew to some extent.

I have been fighting subsidised energy intermittency (https://iea.org.uk/blog/fickle-as-the-wind) and Net Zero (https://www.c4cs.org.uk/book/76/costs-decarbonisation) longer than most. It is irrational to say, in effect, “bad planning and government interventions have screwed up our economy, so more planning and interventions are the way to fix that”.

Yes, the supply of wind and solar electricity does not respond to price signals, except very slowly in the sense that prices incentivise deployment as well as operation. And in the UK's skewed energy market, wholesale market prices have little bearing on the deployment of wind and solar because that is determined almost entirely by the subsidies and other interventions.

But the justification for responsive pricing does not depend on the impact on wind and solar electricity generation. It assists balancing even if there is none. Increasing intermittent generation makes other sources of electricity (generation and storage) all the more important. Their economics is influenced by the wholesale market. And if organisations or homes have the ability to vary their demand according to the level of system stress indicated by the wholesale price, then why shouldn't they? In doing so, they not only profit by moving their demand from expensive to cheap periods, but by reducing system stress, they also benefit everyone else too. If it is voluntary (which it is), why would anyone want to prevent that? And if I'm on Agile and don't vary my usage, I am paying more at the times when the system is most stressed, contributing more to the balancing capacity that we need. So Agile users help whatever they do.

It doesn't matter how much of it there is. However much you get, helps. The option for people to contract for that does not harm the people who don't. It helps them. Envy or economic illiteracy are the only reasons to prevent people from having this choice, if a supplier is willing to offer it.

Agile energy tariffs are not planning or intervention. No one is imposing Agile pricing. No one has to vary their demand if they don’t want to. If you choose to use the tariff, you will probably save money if you are smart. By moving your demand away from periods of high system stress, and paying more for however much peak demand you have left, you help not only yourself, but the energy system. Doing that doesn’t create or stimulate the causes of the imbalances, it mitigates them. Opposition to voluntary Agile pricing is economically illiterate and politically authoritarian. Why shouldn’t we have the option? And criticising defenders of responsive pricing as somehow apologists for Net Zero or intermittent energy is irrational, ahistorical and insulting.

It sometimes seems like opponents of Net Zero think the energy market would have no imbalances otherwise. Demand varies a lot, wherever the energy comes from. That’s especially if you consider all energy, not just electricity, which many amateur energy commentators (and policymakers) often confuse. Supplying peak demand is more expensive than supplying baseload demand, however it is done. If we scrap Net Zero tomorrow, we will still have strong economic benefits from offering price signals that encourage people to think about their energy usage at peak, and about investment in technology to meet that demand.

Yes, let’s stop screwing up our energy systems. Giving people the opportunity to contribute to balancing the system is part of making it better, not worse.