Building or energy conservation?

Saturday, 30 November 2019

All parties are promising to reduce energy demand in buildings. The standard improvements are surprisingly limited (cavity wall insulation saves 7%, loft insulation saves 4%) and 2/3 of the properties are done already. Major improvement requires rebuilding. But at our current rate of demolition/conversion, it takes 22 years to replace 1% of the housing stock.

The UK's decarbonisation strategy has focused myopically on renewable electricity for 30 years, even though electricity is only 20% of our final energy consumption, and the cost per tonne of carbon has been significantly higher in the favoured technologies than for many other options in the cinderella sectors.

As the carbon footprint of electricity generation reduces, the marginal value of further decarbonisation of the grid also reduces. Focus is finally turning to the other 80% of our energy consumption: heat and transport.

There are two angles to approach the decarbonisation of any form of energy: efficiency (i.e. reducing demand) and low-carbon supply for whatever demand remains.

All the parties are promising to reduce energy demand in buildings:

Labour:

upgrade almost all of the UK’s 27 million homes to the highest energy-efficiency standards, reducing the average household energy bill by £417 per household per year by 2030 and eliminating fuel poverty

Conservatives:

We will help lower energy bills by investing £9.2 billion in the energy efficiency of homes, schools and hospitals.

LibDems:

Cut energy bills, end fuel poverty by 2025 and reduce emissions from buildings, including by providing free retrofits for low-income homes, piloting a new subsidised Energy-Saving Homes scheme, graduating Stamp Duty Land Tax by the energy rating of the property and reducing VAT on home insulation.

SNP:

a reduction in VAT on energy efficiency improvements in homes, ending the Treasury’s 20% tax on making people’s homes warmer and greener.

etc.

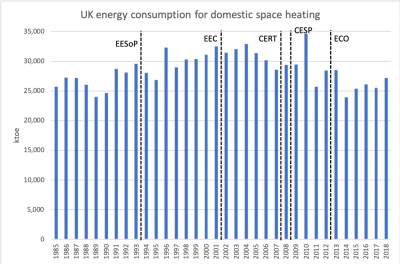

OK, great. Except governments have been running schemes to improve building efficiency for decades, to the point that over two-thirds of homes with cavity walls have been insulated and likewise for lofts. Yet it has barely made a dent in energy consumption in buildings.

They're not proposing a radical departure. They're proposing more of the same, with modest remaining potential to do the same, even though the same isn't very effective.

One reason it's not effective is that these schemes have relied on supply-push (energy suppliers being compelled to install efficiency measures in their customers' properties) rather than demand-pull (consumers installing efficiency measures in order to reduce their bills). In the former case, the incentive is to be no more efficient than required, as any reductions are a direct hit to the revenues of the company funding the improvement. In the latter case, the incentive is to be as efficient as possible, because the person funding the improvement gets the saving from the reduction. Yet all the parties appear to be proposing more of the former approach.

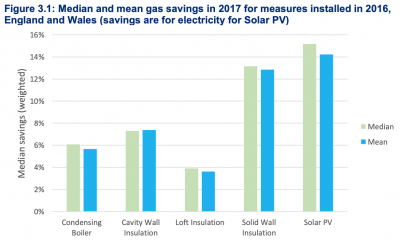

But there is a limit to what can be achieved by retrofit anyway, even with the best of intentions. The government's own statistics estimate that cavity-wall insulation to the prescribed standard reduces gas usage by 7.5% on average. Loft insulation reduces it by 3.8%. Solid wall insulation has a bigger impact at 13%, but a far smaller proportion (around 10%) of solid-wall properties have been insulated than cavity-wall properties, because it is a more complicated and expensive thing to do.

To make a real difference, we would need to replace buildings, not improve them; designing and building from the ground up to have a low energy footprint. Most of the parties also include plans to promote higher efficiency standards in new buildings.

But these are relevant only to the extent that new buildings are built. And if the new buildings are mainly additions to the housing stock, not replacements, then there will be little progress on decarbonising the existing stock.

Unfortunately, we have almost given up demolishing old buildings. In the period from the War to around 1980, we demolished roughly 50,000 dwellings a year (House of Commons Library, Tackling the under-supply of housing in England, Dec 2018). From 1980, the demolitions ground to a halt. There seems to have been a bit of a revival in the early 21st century, but demolitions fell again from 22,000 in England in 2006/7 to 8,000 in 2018/19.

We also convert a handful of buildings each year. But if we add demolitions and conversions, the number of old buildings being replaced by more efficient homes is down to around 13,000 a year (see Table 118 of MHCLG, Live tables on housing supply: net additional dwellings).

There are around 28.4m homes in total in the UK. At 13,000 demolitions or conversions a year, it takes 22 years to replace just 1% of them.

Unless a political party admits that we will have to radically increase the rate of replacement of the housing stock (as well as adding to the housing stock to accommodate the rising population), then promises to improve their efficiency are largely hot air, and budgets to try to do that by the same old means will be largely "spaffed up the wall".

Related blogs